3.5.1 Current electricity

3.5.1.1 Basics of electricity

Charge

- Measured in coulomb (C)

- Charge of 1 electron = \(-1.60 \times 10^{-19} \text{ C}\)

- Scalar quantity

Electric current (I)

- The rate of flow of charge

- \(I = \frac{\Delta Q}{\Delta t}\)

Potential difference (V)

- The energy transferred per unit charge between two points in a circuit

- When a charge of 1 C passes through a p.d. of 1 V, it does 1 J of work

- \(V = \frac{W}{Q}\)

Resistance (R)

- A measure of how difficult it is for charge carriers to pass through a component

- \(R = \frac{V}{I}\)

Capacity

- A measure of the total amount of charge which the battery can push around a circuit

- Commonly measured in ampere-hours (A h)

- 1 Ah = a current of 1 A can flow for 1 hour = 3600 C

Types of charge carriers

- Insulator

- Each electron is attached to an atom and cannot move away from the atom

- Metallic conductor

- Most electrons are attached to metal ions but some are delocalised

- Delocalised electrons can carry charge through the metal

- When a voltage is applied across the metal these conduction electrons are attracted towards the positive terminal of the metal

- Semiconductor

- Number of charge carriers increase with an increase of temperature (electrons break free from the atoms of the semiconductor)

- Resistance fall as temperature rise

3.5.1.2 Current-voltage characteristics

Ohm's law

- The current through a conductor is directly proportional to the potential difference across the conductor provided that temperature and other physical conditions remain constant

- \(V = IR\)

- Not the definition of voltage

Types of different conductors

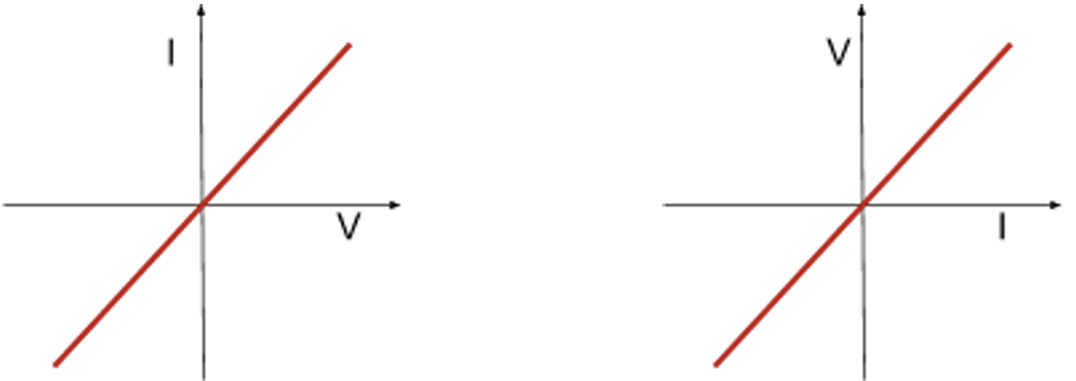

- Ohmic conductor

- Follows Ohm’s law

- Constant resistance as long as temperature and other physical conditions remain constant

- Current-voltage graph will look like a straight line through the origin

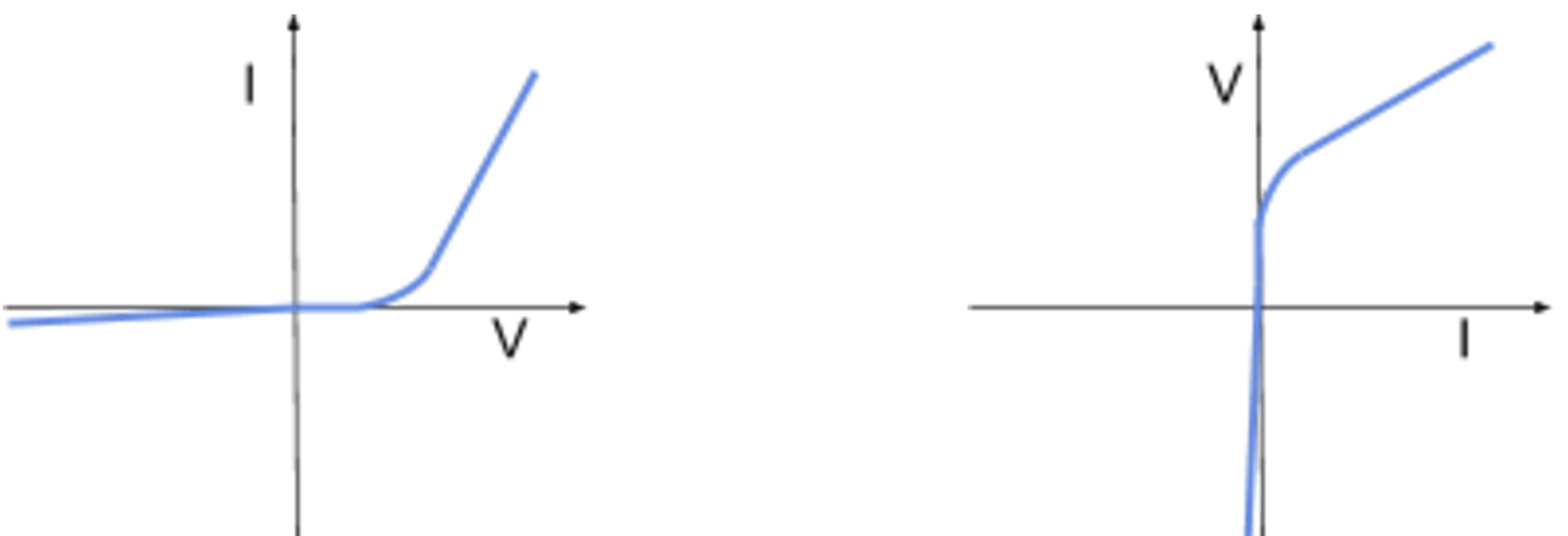

- Semiconductor diode

- Only lets current flow in one direction, converts AC to DC

- Forward biased: allow current to flow easily past the threshold voltage (smallest voltage needed to allow current to flow)

- Reverse biased: the resistance of the diode is extremely high so that only a very small current can flow

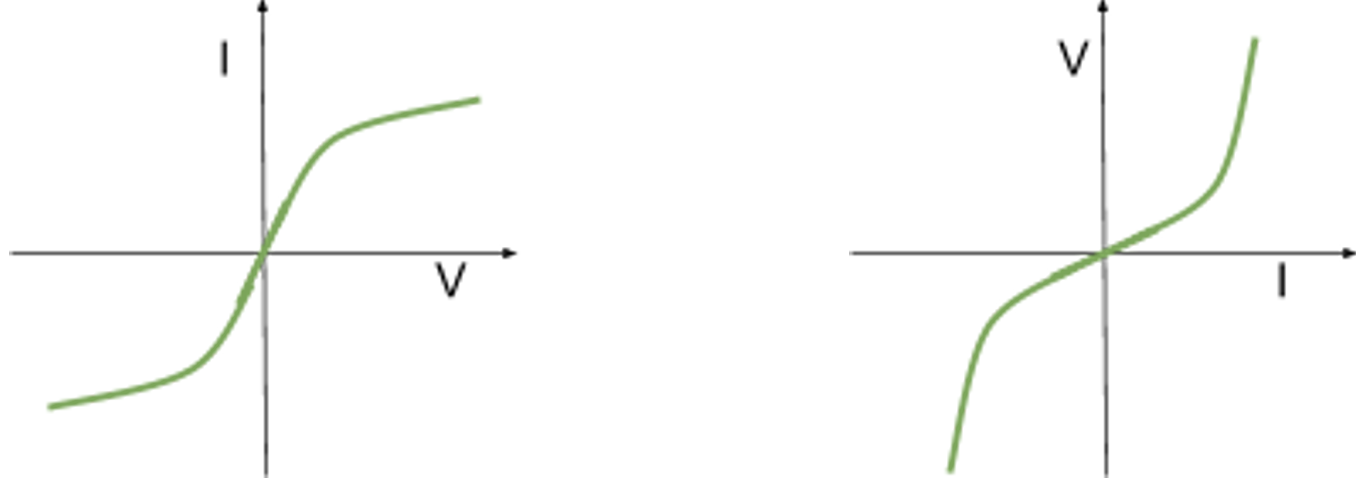

- Non-ohmic conductors e.g. filament lamp

- Ohm's law obeyed initially (a straight line initially)

- Does not have a constant resistance

- As voltage increases current increases

- More electrons flow through the wire per second

- Current heats filament

- Higher rate of collisions between ions in the lattice structure and electrons

- Conducting electrons slow down more and lose more kinetic energy so current falls and resistance increases

- Rate of increase of current is less than if resistance was constant

- As current or voltage increases resistance increases so the gradient is not constant

- Negative voltage and current produces the same effect

Assumptions

- Assume ammeters and voltmeters are ideal unless otherwise stated

- Ammeters can be assumed to have zero resistance

- Voltmeters can be assumed to have infinite resistance

3.5.1.3 Resistivity

Resistivity (\(\rho\))

- Resistance per unit length \(\times\) area of cross section

- \(\rho = \frac{RA}{L}\) or \(R = \frac{\rho L}{A}\)

- Unit = \(\Omega \text{m}\)

Effect of temperature on the resistance of metal conductors

- When the temperature of a metal conductor increases its resistance will increase

- Metal ions gain KE from heating and vibrate more so they take up more space

- More collisions between electrons and metal ions per second so they slow down more

- Current falls so resistance increases

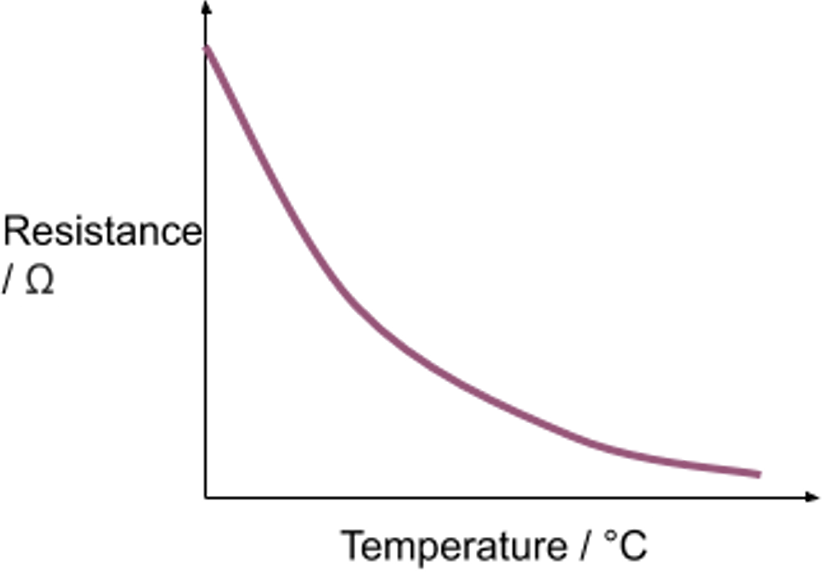

Effect of temperature on the resistance of thermistors

- When the temperature of a thermistor increases, its resistance will decrease

- Increasing the temperature of a thermistor causes electrons to be emitted from atoms = more charge carriers = current increase

Application of thermistors

- Temperature sensors

- Trigger an event to occur once the temperature drops below or reaches a certain value

- e.g. turn on the heating once room temperature drops below a specific value

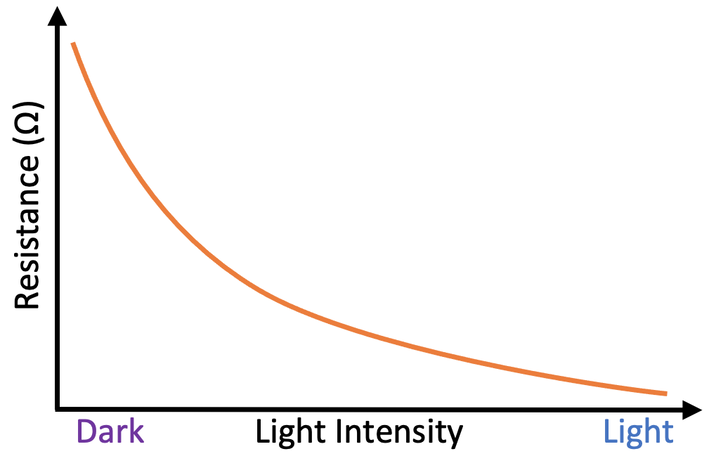

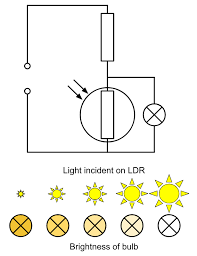

LDR

- Resistance decreases as light intensity increases

- Used to trigger certain events

Superconductivity

- A property of certain materials which have zero resistivity at and below a critical temperature (\(T_{c}\)) which depends on the material

- Resistivity decreases as temperature decreases

- Zero resistivity = zero resistance

- Critical temperature normally extremely low (close to 0 K)

Applications of superconductors

- Power cables

- Reduce energy loss due to heating to zero during transmission

- Production of strong magnetic fields

- Do not require a constant power source

- Used in maglev trains / certain medical applications

Resistance of a wire

- Normally assumed to be 0 so no PD is lost between 2 points on a wire with no resistors between them

- The assumption can break down if the current is high / resistance in the rest of the circuit is low

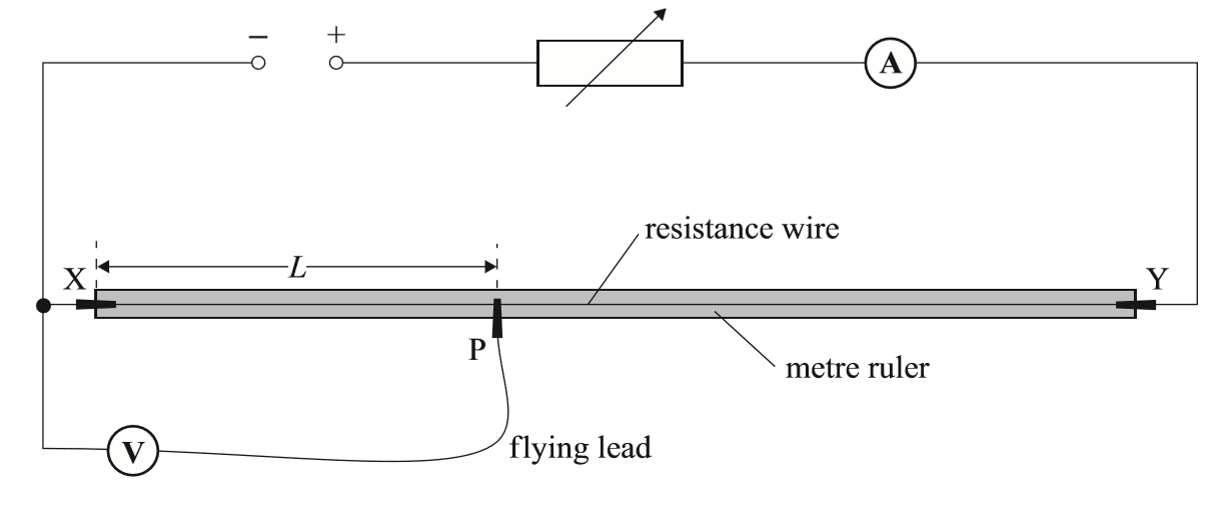

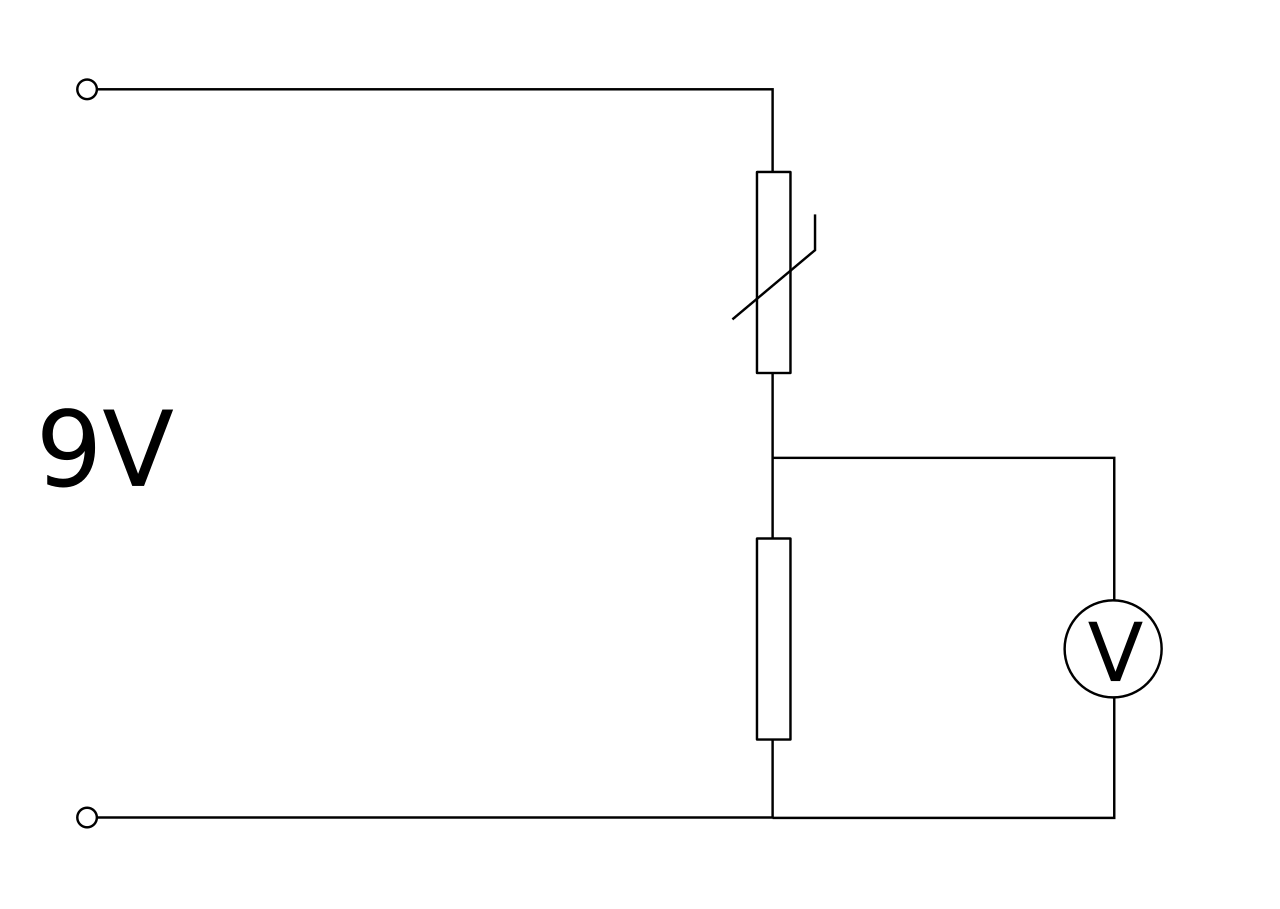

Required practical 5 - determining wire resistivity

Method

- Set up the circuit as shown

- Connect the flying lead to the wire so that 0.10 m of the wire has its resistance measured

- Switch on the power supply and adjust the voltage of it so that the current in the circuit is 0.50 A

- Turn off the power supply between readings so the wire does not heat up and increase in resistance

- Measure and record the length and voltage across the wire by taking reading on the voltmeter

- Move the flying lead to increase the length by 0.10 m and repeat the measuring process for lengths up to 1.00 m

- Repeat the experiment twice for each reading and calculate an average voltage at each length

- Calculate resistance at each length by \(R = \frac{V}{I}\)

- Plot a graph of resistance against length

- Resistivity = gradient \(\times\) cross sectional area (gradient = \(\frac{\rho}{A}\))

Errors

- Random Errors

- The current flowing through the wire will cause its temperature to increase and increase its resistance and resistivity

- Only allow small currents to flow through the wire so the temperature is kept constant and low

- The power supply should be switched off between readings so its temperature doesn't change its resistance

- Make at least 5-10 measurements of the diameter of the wire with the micrometer screw gauge and calculate an average diameter to reduce random errors in the reading

- The wire should be free from kinks and held straight so the measurement of the length is as accurate as possible.

- The current flowing through the wire will cause its temperature to increase and increase its resistance and resistivity

- Systematic errors

- Zero error when measuring wire length

Safety Considerations

- When there is a high current, and a thin wire, the wire will become very hot

- Make sure never to touch the wire directly when the circuit is switched on

- Switch off the power supply right away if you smell burning

- Make sure there are no liquids close to the equipment, as this could damage the electrical equipment

3.5.1.4 Circuits

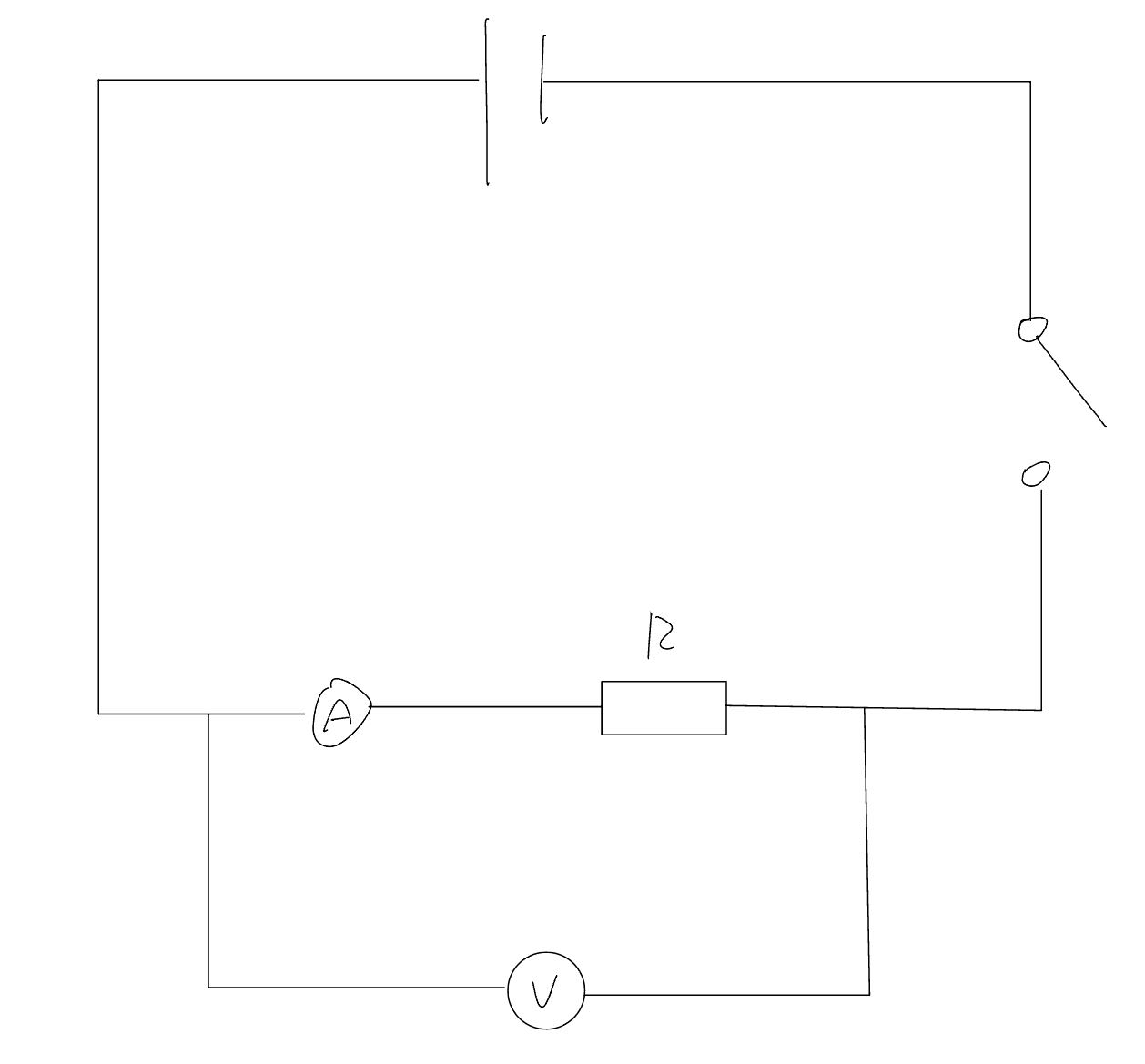

Circuit symbols

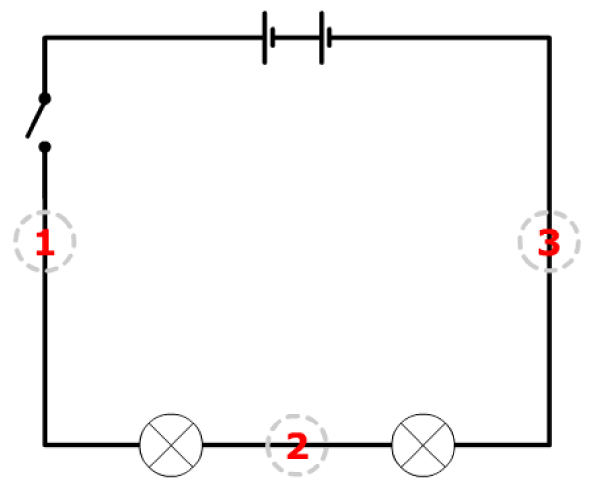

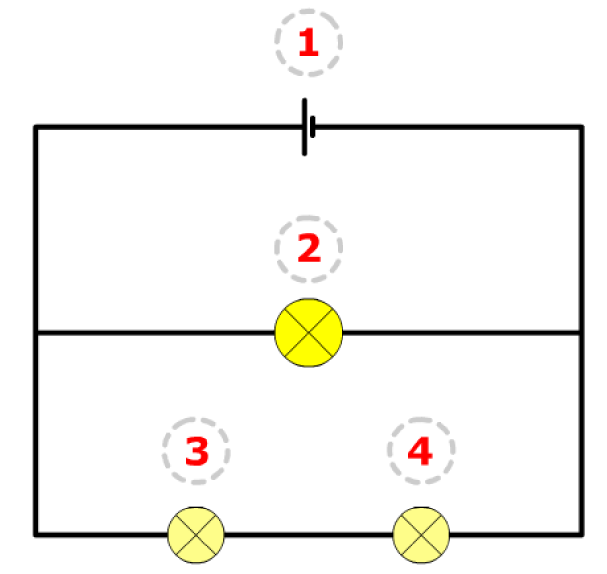

Series circuit properties

- The current is the same at all points

- ① = ② = ③

- The sum of potential differences across the components is equal to the total EMF of the power supply

- ① = ② + ③

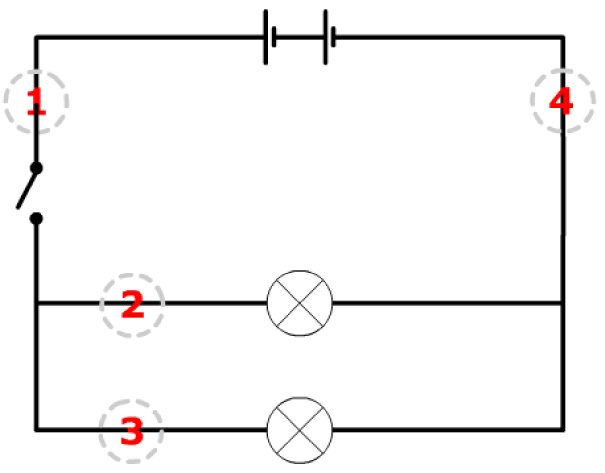

Parallel circuit properties

- The current splits up

- Some of it going one way and the rest going the other

- Total current in the circuit = sum of the currents in the branches

- ① = ② + ③ = ④

- Total voltage of a parallel circuit has the same value as the voltage across each branch

- ① = ② = ③ + ④

Total voltage of cells

- Cells joined in series

- \(V_{T} = V_{1} + V_{2} + V_{3} + \ldots\)

- Identical cells joined in parallel

- Total voltage = voltage of one cell as current is split equally between branches so overall pd is the same as if the total current was flowing through a single cell

- \(V_{T} = V_{1} = V_{2} = V_{3} = \ldots = \epsilon - \frac{Ir}{n} = \text{emf} - \frac{\text{total current of the circuit} \times \text{internal resistance of each cell}}{\text{number of cells}}\)

- Total internal resistance = calculated in the same way as other parallel circuits

- Act like one cell but with reduced internal resistance

Advantages of cells joined in parallel

- Reduce the combined internal resistance of the cells - reduce lost volts

- Less power drawn from each cell so it lasts longer

Total resistance calculation

- In series

- \(R_{T} = R_{1} + R_{2} + R_{3} + \ldots + R_{n}\)

- In parallel

- \(\frac{1}{R_{T}} = \frac{1}{R_{1}} + \frac{1}{R_{2}} + \frac{1}{R_{3}} + \ldots + \frac{1}{R_{n}}\)

Power (\(P\)) and energy (\(E\))

- \(P = IV = \frac{V^{2}}{R} = I^{2}R\)

- \(E = Pt = IVt\)

Kirchhoff's laws

- In DC circuits

- Kirchhoff's first law (conservation of charge)

- The total current flowing into a junction is equal to the current flowing out of that junction

- No charge is lost at any point in the circuit

- Kirchhoff's second law (conservation of energy)

- The sum of all the voltages in a series circuit is equal to the battery voltage

- No energy is lost at any point in a circuit

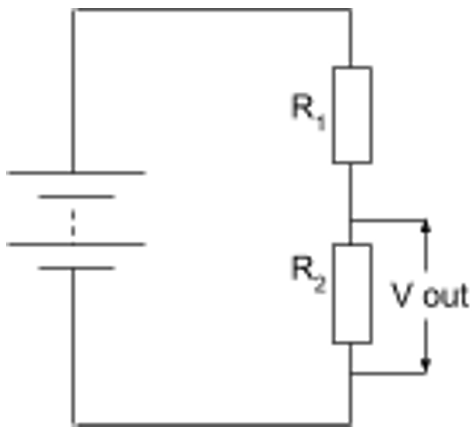

3.5.1.5 Potential divider

Potential divider

- Circuits which produce an output voltage as a fraction of its input voltage

- Has several resistors in series connected across a voltage source

- Used to supply constant or variable potential difference from a power supply

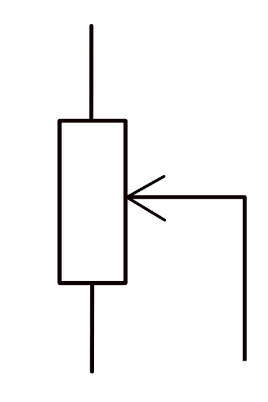

Using variable resistors

- Potential divider supply a variable pd

- Use variable resistor as one of the resistor in series

- Vary the resistance across = vary pd output

Using thermistor / LDR

- Resistance decreases as temperature / light intensity increases

- Used to trigger certain events

Change in voltage across one resistor

- Resistance stayed constant

- Current increase / decrease \(\rightarrow\) voltage across changes

- Resistance changed

- The resistor has increased / decreased share of total resistance

- New current is the same in both resistors

- The resistor gets a larger / smaller share of the EMF

3.5.1.6 Electromotive force and internal resistance

Internal resistance of batteries

- The resistance of the materials within the battery

- Caused by electrons colliding with atoms inside the battery so some energy is lost before electrons leave the battery

- Represented as a small resistor inside the battery

Terminal pd (\(V\))

- Pd across the resistor(s)

- \(V = \epsilon - Ir\)

Lost volts (\(v\))

- Pd across the internal resistor in the battery

- = energy wasted by the cell per coulomb of charge

Electromotive force

- The energy converted (from chemical) to electrical energy by a cell for per coulomb of charge that passes through it

- Can be measured by measuring the voltage across a cell using a voltmeter when there is no current running through the cell

- \(\epsilon = \frac{E}{Q} = \frac{\text{electrical energy transferred}}{\text{charge}}\)

- \(\epsilon = V + v = I(R + r) = \text{current} \times (\text{load resistance} + \text{internal resistance})\)

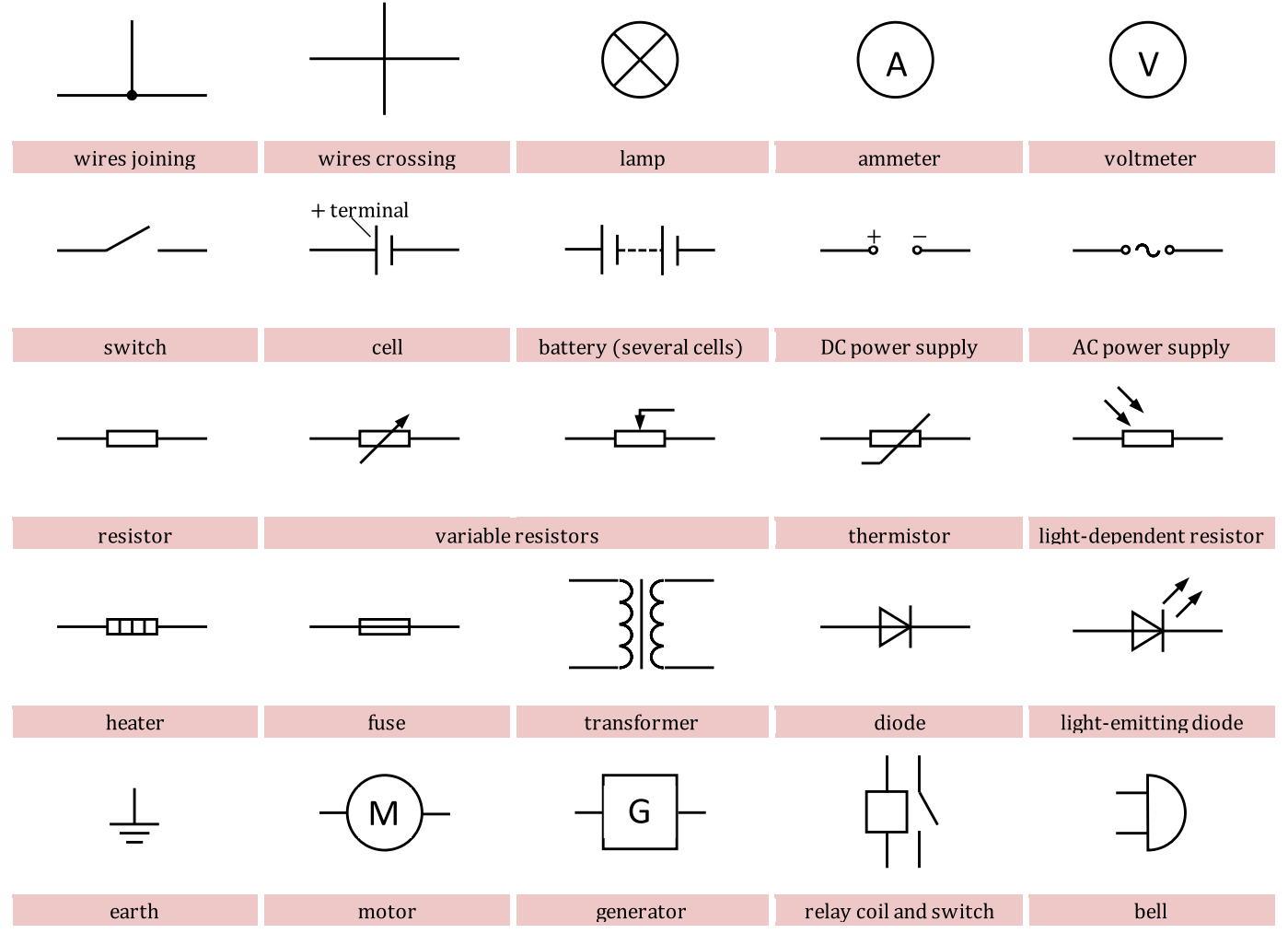

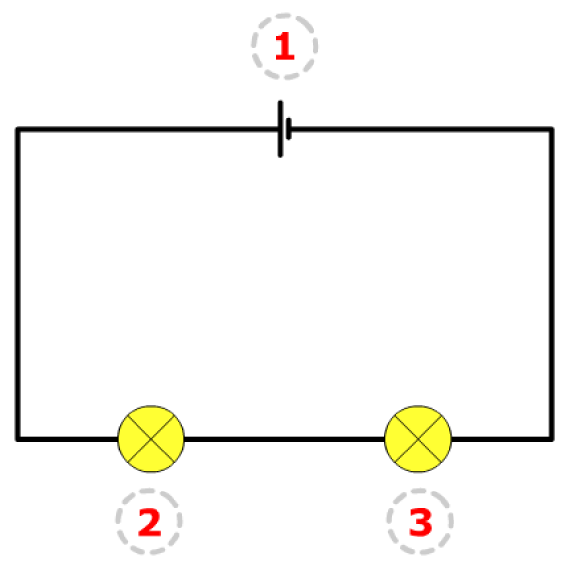

Required practical 6 - finding the EMF and internal resistance of a cell

Method

- Set up the circuit as shown above with 2 (1.5V) cells connected in series

- Connect a voltmeter across the resistor to measure the load voltage

- Close the switch so that the current flows in the circuit

- Record the ammeter and voltmeter readings

- Open the switch to cut off the current and prevent heating in the circuit

- Replace the resistor with a different resistor with a different resistance and repeat the measuring process

- Use at least 5 different resistors with different resistances

- Repeat the experiment 2 more times for each resistor and calculate the mean current and voltage

- Plot a graph of load voltage against current

- EMF of the cell is the y-intercept of the graph while the internal resistance of the cell is the magnitude of the gradient of the graph

Safety

- Another resistor can be included in series with the other to avoid high currents which could be dangerous and make the wires get hot

Improvements / controls

- Only close the switch for as long as it takes to read off each pair of readings

- Prevent the internal resistance of the battery or cell from changing during the experiment due to heating

- Use fairly new batteries/cells

- The emf and internal resistance of run down batteries can vary during the experiment