3.1.1 Periodicity

Definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Periodicity | A repeating trend in physical and chemical properties of the elements across the periodic table. |

| Groups | A vertical column in the periodic table. Elements in a group have similar chemical properties and their atoms have the same number of outer shell electrons. |

| Periods | A horizontal row in the periodic table. Elements show trends in properties across a period. |

| Shielding effect | The repulsion between electrons in different inner shells. Shielding reduces the net attractive force between the positive nucleus and the outer shell electrons. |

| Metallic bonding | The strong electrostatic attraction between the regularly arranged metal cations and the delocalised valence electrons between them. |

| Delocalised electrons | Electrons shared between more than two atoms / ions. |

| Giant metallic lattice | A three dimensional structure of positive ions and delocalised electrons, bonded together by strong metallic bonds. |

| Giant covalent lattice | A three dimensional structure of atoms, bonded together by strong covalent bonds. |

The periodic table

History

- Then

- Mendeleev arranged the elements in order of atomic mass

- Swapped elements to arrange them into groups of similar properties

- Gaps left where he thought elements would be found

- Predicted properties for missing elements

- Newly discovered elements filled in the gap and matched the predicted properties

- Now

- Arranged in increasing atomic number

- In vertical columns (groups) with same number of outer electrons + similar properties and horizontal rows (periods) giving number of highest energy electron shell

Arrangement

- In the order of increasing atomic number

- Periodicity: in periods showing repeating trends in physical and chemical properties e.g. metals \(\rightarrow\) non-metals

- In groups with similar properties

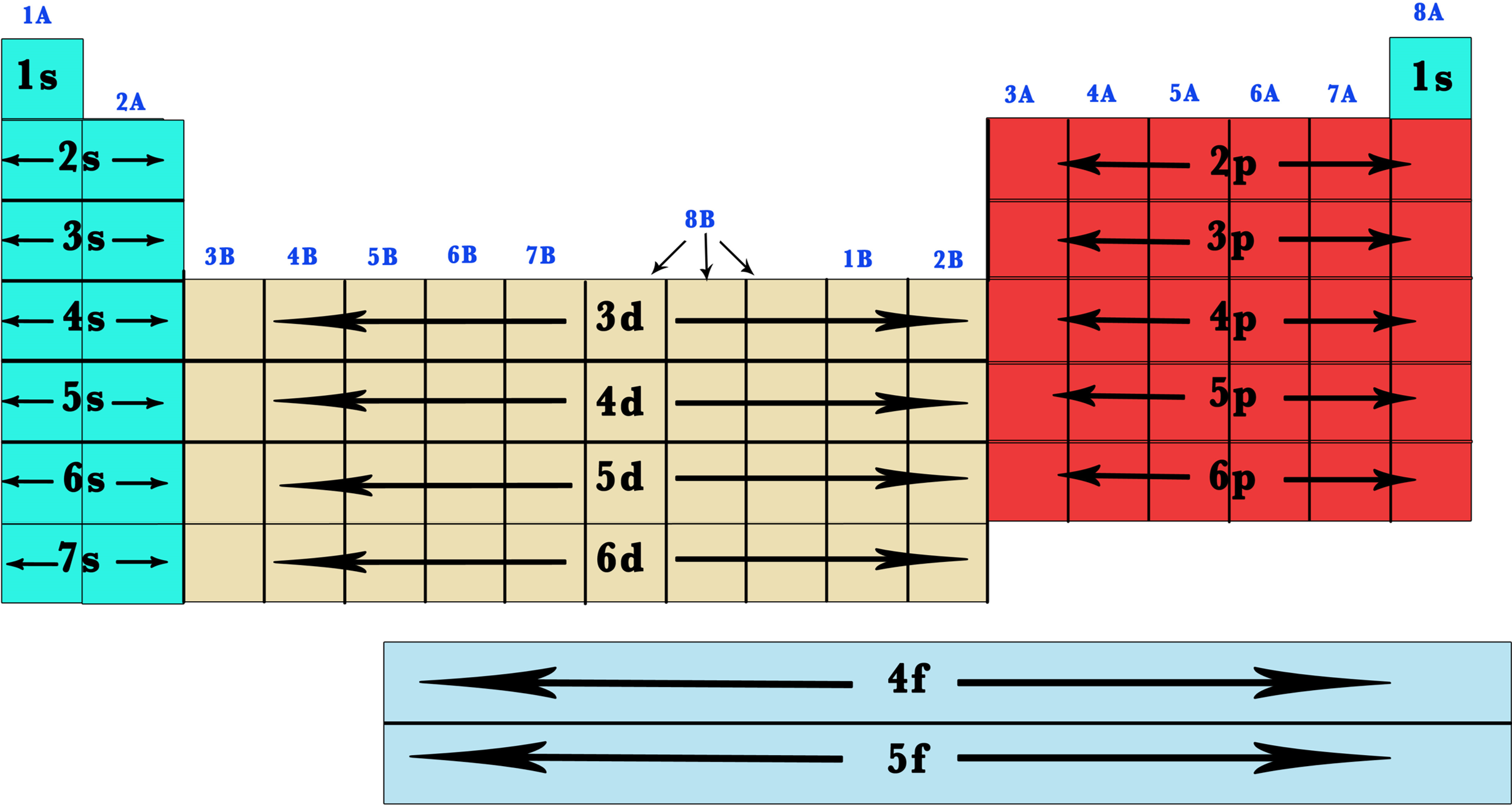

Electron configuration pattern

- Across period

- Each period starts with an electron in a new highest energy shell

- Period 2: \(2s\) fills \(\rightarrow\) \(2p\) fills

- Period 3: \(3s\) fills \(\rightarrow\) \(3p\) fills

- Period 4: only \(4s\) and \(4d\) occupied in shell

Blocks

- s/p/d/f-block meaning: the highest energy electron is in a s/p/d/f-orbital

- S, p, d and f block

Name of groups

| Group number | Name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Alkali metal |

| 2 | Alkaline earth metals |

| 3-12 | Transition elements |

| 15 | Pnictogens |

| 16 | Chalcogens |

| 17 | Halogens |

| 18 | Noble gases |

Ionisation energy

First ionisation energy

- Energy required to remove one electron from each atom in one mole of gaseous atoms of an element, forming one mole of gaseous 1+ ions

- Unit = \(kJ \cdot mol^{-1}\)

- Equation: \(X(g) \rightarrow X^+(g) + e^-\)

Factors affecting ionisation energy

- Atomic radius

- Greater distance between nucleus and outer electrons = less nuclear attraction

- Large effect on ionisation energy as force of attraction falls sharply with increasing distance

- Nuclear charge (weakest effect, outweighed)

- More protons in nucleus (greater nuclear charge) = greater attraction between the nucleus and the outer electrons = increase in ionisation energy

- Electron shielding

- Shielding effect: electrons are negatively charged so inner shell electrons repel outer-shell electrons

- Reduces the attraction between nucleus and outer electrons \(\rightarrow\) reduce ionisation energy

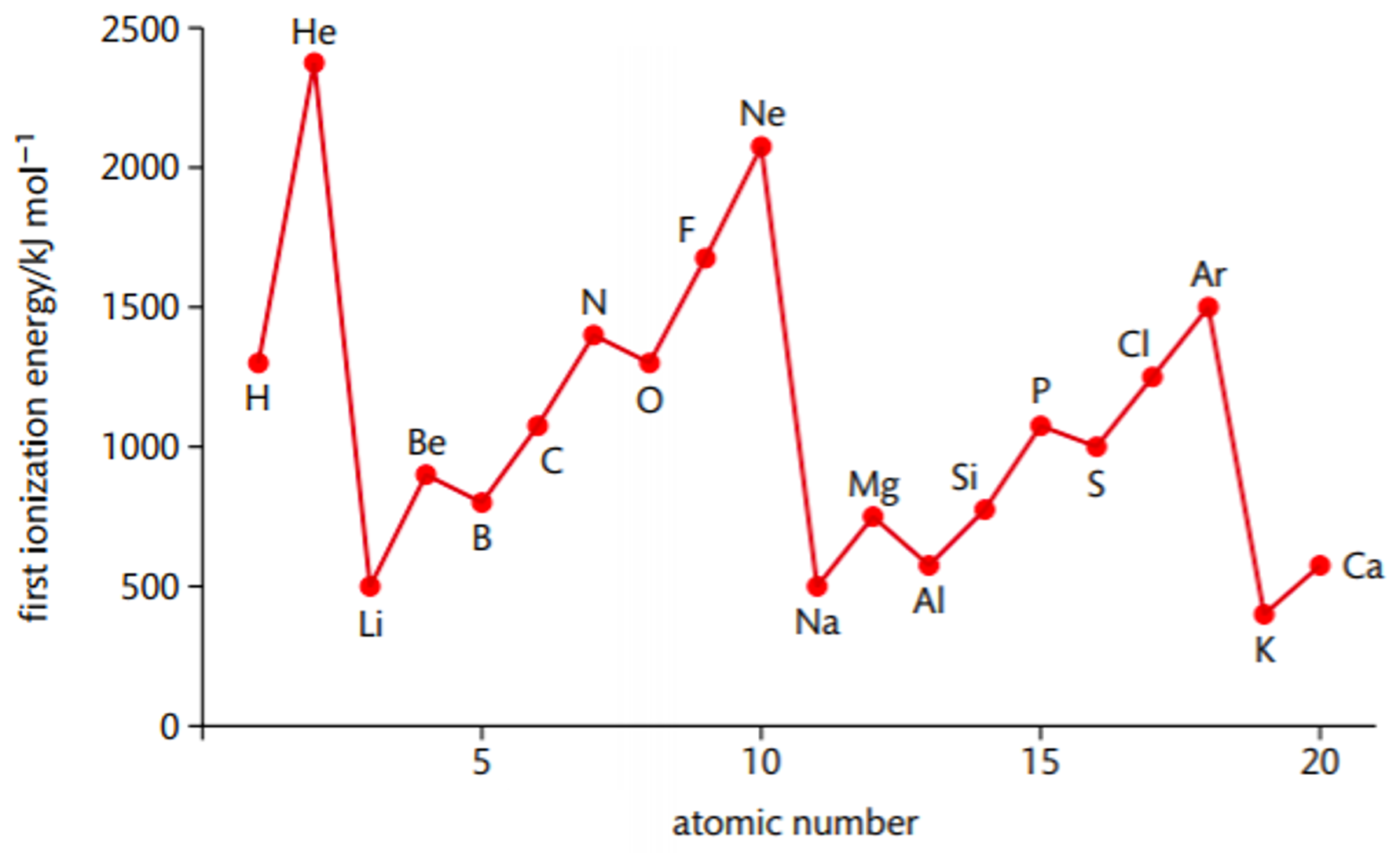

First ionisation energy trends across a period

- Increases across a period

- Nuclear charge increases

- Same number of shells so similar shielding

- Atomic radius decreases

- Nuclear attraction increases \(\rightarrow\) first ionisation energy increases

- Falls when the p sub-shell is starting to be filled (e.g. \(Li \rightarrow Be\))

- \(2p / 3p\) sub-shell has a higher energy than \(2s / 3s\) sub-shell so the electron is easier to remove

- Still larger than IE before the decrease

- Falls when pairing of electrons in p sub-shell starts (e.g. \(N \rightarrow O\))

- Paired electrons in one of the p orbitals repel one another so it is easier to remove an electron from the atom

- Still larger than IE before the decrease

First ionisation energy trend down a group

- Decrease down a group

- Atomic radius increases

- More inner shells so shielding increases

- Increase in atomic radius and shielding outweighs the increasing nuclear charge

- Nuclear attraction on outer electrons decreases \(\rightarrow\) first ionisation energy decreases

Successive ionisation energy pattern

- Equation: e.g. \(Mg^+(g) \rightarrow Mg^{2+}(g) + e^-\)

- Larger than the previous one

- After the first electron is lost the remaining electrons are pulled closer to the nucleus

- Nuclear attraction on the remaining electrons increases so more energy needed

- Large increase when shell change

- Shell closer to the nucleus as atomic radius drops

- Less shielding present as there are now less inner shells between electron & nucleus

- Stronger nuclear attraction so more energy needed

- Going to a more inner shell = extremely large increase

- Smaller but still large increase when going to a new sub-shell / sub-shell become half filled

- Can be used to work out the number of electrons in each shell + group number of the element

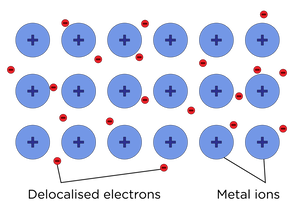

Metallic bond

Metallic bonding structure

- Regularly arranged metal cations sitting in a sea of delocalised electrons

- Each atom donate its negative outer shell electrons to a shared pool of electrons which are delocalised throughout the whole structure

- Cations left behind = nucleus + inner shell electrons

- Cations are fixed in position

- Delocalised electrons are mobile and free to move throughout the structure

- Forms a giant metallic lattice

Properties of metals

- All conduct electricity

- Delocalised electrons can move through the structure and carry charge through the structure when a voltage is applied across a metal

- More delocalised electrons \(\rightarrow\) more electrons can move \(\rightarrow\) better conductivity

- Conducts electricity both in solid state and when molten

- Most have high melting and boiling points

- Depends on the strength of metallic bonds

- Greater cation charge = stronger attractive forces as more electrons are delocalised and forces between electrons + cations are stronger

- Larger ions = weaker attractive forces due to larger atomic radius decreasing the charge density

- High temperature needed to provide the large amount of energy to overcome strong electrostatic attraction between the cations and the electrons

- Melting and boiling points decrease down the group

- Depends on the strength of metallic bonds

- Dissolve in liquid metals only

- Similar force between particles

- Any interaction between polar / non-polar solvent + solute lead to a reaction rather than dissolving

- Forces between particles are too large so it is not energetically favourable for them to mix

Giant covalent structures

Giant covalent structures

- Boron, carbon allotropes, and silicon (\(Si\), \(SiO_2\), \(SiC\))

- A network of atoms bonded by strong covalent bonds to form a giant covalent lattice

Diamond / silicon

- 4 outer shell electrons of each atom form 4 covalent bonds with other carbon / silicon atoms

- Tetrahedral structure

- 109.5° bond angle due to electron-pair repulsion

- High melting and boiling points

- Atoms held together by strong covalent bonds

- High temperatures are needed to provide the large quantity of energy needed to break the strong covalent bonds

- Non-conductors of electricity

- All 4 outer-shell electrons involved in covalent bond so no charged particles or mobile ions are available for conducting electricity

Graphite

- Flat 2D sheets of hexagonally arranged carbon atoms (trigonal planar 120°)

- Layers bonded by weak London forces \(\rightarrow\) they can slide over each other easily so graphite is soft

- High melting and boiling points

- Atoms held together by strong covalent bonds

- High temperatures are needed to provide the large quantity of energy needed to break the strong covalent bonds

- Can conduct electricity

- One electron from each carbon atom is delocalised and is available for conductivity

Graphene

- Single layer of graphite

- Hexagonally arranged (trigonal planar 120°) carbons

- Very hard as there are no points of weakness in the structure

- One of the thinnest + strongest material in existence (atoms held together by strong covalent bond)

- High melting and boiling points

- Atoms held together by strong covalent bonds

- High temperatures are needed to provide the large quantity of energy needed to break the strong covalent bonds

- Can conduct electricity

- One electron from each carbon atom is delocalised

- They can move and conduct electricity

Applications of graphene

- Electronics

- Flexible displays

- Wearables

- Other next-generation electronic devices

Periodic trends in properties

Atomic radii trend across a period

- Atomic radii decreases across the period

- Positive charge in nucleus and negative charge in the outer shell both increases

- Shielding remains similar as the number of shells doesn't change

- The attraction between the nucleus and the outer electrons increases

Melting / boiling point trend across a period

- Increases from Group 1 to 14

- Sharp decrease between Group 14 to 15 - change from giant to simple molecular structures

- Comparatively low from Group 15 to 18

- The exact boiling points depend on the type of covalent bonding

- Giant covalent bonding = very high melting and boiling points

- Simple covalent bonding = depends on strength of intermolecular forces (London forces) which depends on the mass of the nucleus

- Smaller molecular radius = lower boiling points (hence Group 18 has the lowest boiling points)